Cranberry juice

Cranberry juice

URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS (UTI)

|

|

|

|

Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are common in children. By 5 years old, about 8% of girls and about 1% to 2% of boys have had at least one. In older children, UTIs may cause obvious symptoms such as burning or pain with urination (peeing). In infants and young children, UTIs may be harder to detect because symptoms are less specific. In fact, fever is sometimes the only symptom.

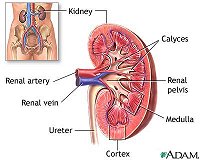

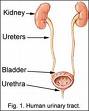

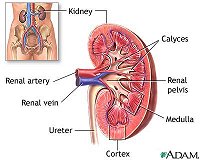

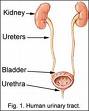

Most UTIs are caused when bacteria infect the urinary tract. The urinary tract is made up of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra, and each plays a role in removing liquid waste from the body. The kidneys filter the blood and produce urine; the ureters carry the urine from the kidneys to the bladder; and the bladder stores the urine until it is eliminated from the body through the urethra.

An infection can occur anywhere along this tract, but the lower part - the urethra and bladder - is most commonly involved. This is called cystitis. If the infection travels up the ureters to the kidneys, it's called pyelonephritis and it's generally more serious.

Although bacteria aren't normally found in the urine, they can easily enter the urinary tract from the skin around the anus (the intestinal bacteria E. coli is the most frequent cause of UTIs). Many other bacteria, and some viruses, can also cause infection. Rarely, bacteria can reach the bladder or kidneys through the blood.

UTIs occur much more frequently in girls, particularly those around the age of toilet teaching, because a girl's urethra is shorter and closer to the anus. Uncircumcised boys younger than 1 year also have a slightly higher risk of developing a UTI. Other risk factors that increase a child's chance of developing a UTI include:

UTIs are highly treatable, but it's important to catch them early. Undiagnosed or untreated UTIs can lead to kidney damage, especially in children younger than 6.

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of UTIs vary depending on the age of the child and on which part of the urinary tract is infected. In younger children and infants, the symptoms may be very general. The child may seem irritable, begin to feed poorly, or vomit. Sometimes the only symptom is a fever that seems to appear for no reason and doesn't go away.

In older children and adults, signs and symptoms can reveal which part of the urinary tract is infected. In a bladder infection, the child may have:

Many of these symptoms are also seen in a kidney infection, but the child often appears more ill and there is more likely to be fever with shaking chills, pain in the side or back, severe fatigue, or vomiting.

Contagiousness

Bacterial UTIs are not contagious.

Prevention

In infants and toddlers, frequent diaper changes can help prevent the spread of bacteria that cause UTIs. When children begin to self care, it's important to teach them good hygeine. After every bowel movement, girls should remember to wipe toilet tissue from front to rear - not rear to front - to prevent germs from spreading from the rectum to the urethra. Children should also be taught not to "hold it in" when they have to go, because urine that remains in the bladder gives bacteria a good place to grow.

School-age girls should avoid bubble baths and strong soaps that might cause irritation, and they should also wear cotton underwear instead of nylon because it's less likely to encourage bacterial growth. Other ways to decrease the risk of UTIs include drinking enough fluids and avoiding caffeine, which is reported to irritate the bladder.

Any child diagnosed with VUR should follow their doctor's treatment plan to prevent recurrent UTIs.

Duration

Most UTIs are cured within a week with proper medical treatment. Recurrences are common in certain children with urinary abnormalities, children who have problems emptying their bladders (such as children with spina bifida), or children with very poor toilet and hygiene habits.

Diagnosis

After performing a physical exam and asking about symptoms, your child's doctor may take a urine sample to check for and identify bacteria causing the infection. How a sample is taken depends on how old your child is. Older children may simply need to urinate into a sterile cup. For younger children in diapers, a plastic bag with adhesive tape may be placed over their genitals to catch the urine. However, urine that comes in contact with the skin may become contaminated with the same bacteria causing the infection, so a catheter is usually preferred. This is when a thin tube is inserted into the urethra up to the bladder to get a "clean" urine sample.

The sample may be used for a urinalysis (a test that microscopically checks the urine for germs or pus) or a urine culture (which attempts to grow and identify bacteria in a laboratory). Knowing what bacteria are causing the infection can help your child's doctor choose the best medication to treat it.

Most children with a UTI recover just fine, but some of them - especially those who are very young when they have their first infection or those who have recurrent infections - may need further testing to rule out abnormalities of the urinary tract. If your child's doctor suspects an abnormality, he or she may order special tests, such as an ultrasound of the kidneys and bladder or X-rays that are taken during urination (called a voiding cystourethrogram, or VCUG). These tests, as well as other imaging studies, can check for problems in the structure or function of your child's urinary tract. Your child may also be referred to a urologist (a doctor who specializes in diseases of the urinary tract).

Treatment

UTIs are treated with antibiotics. The type of antibiotic used and how long it must be taken will depend on the type of bacteria that is causing the infection and how severe it is. After several days of antibiotics, your child's doctor may repeat the urine tests to confirm that the infection is gone. It's important to make sure the infection is cleared because an incompletely treated UTI can recur or spread.

If a child is having severe pain with urination, the doctor may also prescribe a medication that numbs the lining of the urinary tract. This medication temporarily causes the urine to turn orange, but don't be alarmed - the color is of no significance.

Give prescribed antibiotics on schedule for as many days as your child's doctor directs. Keep track of your child's trips to the bathroom, and ask your child about symptoms like pain or burning on urination. These symptoms should improve within 2 to 3 days after antibiotics are started.

Take your child's temperature once each morning and each evening, and call your child's doctor if it rises above 101 degrees Fahrenheit (38.3 degrees Celsius), or above 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius) rectally in infants. Encourage your child to drink plenty of fluids, but avoid beverages containing caffeine, such as soda and iced tea.

Children with a simple bladder infection are usually treated at home with oral antibiotics. However, children with a more severe infection may need to be treated in a hospital, where they can get antibiotics injected or intravenously (delivered through a vein right into the bloodstream). Children tend to be hospitalized for UTI if:

Children diagnosed with reflux of urine (VUR) will need to be followed closely by the doctor. Treatment of VUR may include medications or, less commonly, surgical procedures. Most children outgrow mild forms of VUR, but some children with VUR can develop kidney damage or kidney failure later in life.

When to Call Your Child's Doctor

Call your child's doctor immediately if your child has an unexplained fever with shaking chills, especially if accompanied by back pain or any type of discomfort during urination.

Also call your child's doctor if your child has any of the following:

In infants, call your child's doctor if your child has a fever, feeds poorly, vomits repeatedly, or seems unusually irritable.

Disclaimer: This information is not intended be a substitute for professional medical advice. It is provided for educational purposes only. You assume full responsibility for how you choose to use this information.

Reviewed by: Larissa Hirsch, MD

Date reviewed: November 2006

Originally reviewed by: Steven Dowshen, MD, and Joel Klein, MD